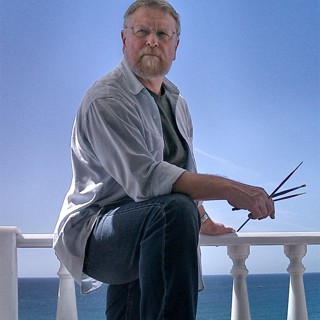

Michael Parkes

MICHAEL PARKES: THE MAGIC AND THE MYSTERY

Beauty is not a concept that is going to get anyone much respect in the present climate of art opinion. A group of young critics were delivering for television their assessment of the four finalists in Britain’s famous (or notorious, depending where you are coming from) Turner Prize for contemporary art. The first three were received with due deference, but the last, a set of very soigné video installations, was greeted with derision. “It’s elegant,” they chorused; “It’s shapely. It looks beautiful. They can’t be serious if they think anyone could possibly consider this as art!”

No, even in painting (which, needless to say, none of the Turner Prize finalists were practising) traditional values in art tend to get rather short shrift. It all rather reminds one of the film producer in Sunset Boulevard who, when urged to read the hero’s stories because they are moving and true, snaps back angrily “Who wants moving; who wants true?” Well, mercifully, in painting and the visual arts at least there are still many ready to buck the trend. Art lovers and collectors, perhaps, more than art makers. But as long as there are a few in the world like Michael Parkes, we do not have to lose hope just yet.

Michael Parkes is now in his late seventies: no age at all when you think of Titian still trying out revolutionary ideas in his nineties, or Hokusai, in his own words “an old man mad about painting”. But mature enough to have reached the years of discretion, to be glimpsing the possibility that the Sturm und Drang of youth might now begin to fit into a comfortable perspective. In Parkes’s case it looks like the perfect combination: the vigour and vaulting invention of youth, philosophised with the unquestioning ease of riper years.

Of course, Parkes has always been exceptional among his generation in his unflagging pursuit of beauty. The goddesses/angels/women in his paintings are always what in any other hands one would call impossibly beautiful. “In your dreams, fella!” one might be tempted to cry. But if the dreamer happens to be called Michael Parkes, then everything is fine, for he has the total conviction in his own dreams, backed up by the requisite crystalline sureness of technique, which enforces belief in the observer. Some call it Magic Realism, and both parts of the equation apply, in that the realism of the treatment is undoubtedly dusted with magic.

Realism, after all, is a technique, not a religion – though it does entail an act of faith. Faith on the part of the spectator, who has to suspend disbelief that this two-dimensional construct is actually living and breathing in three. And faith on the part of the artist, in that he must believe so intensely in his own creation that even the most fantastic beast is endowed with a credible anatomy, the most flawless beauty given somehow that touch of humanity which compels complete acceptance.

Parkes has always said, in effect, “Welcome to my world”. And moreover, made us all feel welcome to it. Which is probably a more difficult task than it seems. Until very recently, the outside world has not been too susceptible to fantasy. Only if it has been decked out in the trappings of science fiction, as in the first Star Wars trilogy, has it seemed vaguely respectable and adult (in, possibly, a schoolboyish sort of way) to appreciate it. But Parkes’s kind of fantasy has little to do with science fiction: it is for grown-ups. Its references are all to do with myth and legend, taking their place in a land, or rather a firmament, where otherworldly exquisites mingle with fabulous beasts in a prelapsarian paradise. Not, in other words, the fantasy world of Terminator, or even Silent Running, but something more to the understanding of those who appreciate the Lord of the Rings or Narnia trilogies.

At first glance, it is difficult to imagine that Parkes began his public career as an Abstract Expressionist. Less so when you take into consideration the fact that Parkes has always been quite comfortable in his own time – or at least, known how to deal with it. When he was a student, at the University of Kansas in the 1960s, all his teachers were of an age to have been dazzled by the first manifestations of Abstract Expressionism in New York, and to hand on their sense of wonder at it all to their pupils.

And from the beginning Parkes was aware of and responsive to the often-overlooked mystical side of the movement. Not for nothing is one of Mark Rothko’s later series of darkly glowing colour-field paintings known as The Chapel. The fluttering, whirling calligraphy of Jackson Pollock or the monumental shapes of Robert Motherwell aspire, in their Zen sparseness and directness, to capture the essence. As Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning moved closer to abstraction, their earlier subject matter left luminous traces in their work, as though they were still painting creatures and objects – but just not quite creatures and objects as we have ever known them.

Creatures and objects, but not quite as we have ever known them: that would be a good description of Parkes’s subject matter. But if that makes the transitions in his art sound easy, it is far wide of the mark. He began with one immense advantage: he could draw even before he could read and write, and even as a small child, he was uniquely well qualified, when he did the classic childhood thing of thinking, and then drawing lines round his thoughts, to come up with something that even tiresome, unimaginative adults could recognise and appreciate.

Other aspects of Parkes’s childhood were not so advantageous – or not necessarily so. He was an only child, which often leads to children being dreamy and introspective, especially if their family lives in a small community with not much social life going on.. The town where Parkes was raised, Canalou, Missouri, had fewer than 300 inhabitants,but it did have a school, where reading and art were encouraged. And it did have a Last Picture Show-type movie theatre, even if it showed mostly a diet of Hopalong Cassidy Westerns and Z-level monster movies which it would be flattering to call science fiction.

Nonetheless, Parkes managed to be inspired by at least one of the latter, if not many of the former. He was carried away, imaginatively rather than literally, by the It that Came from Outer Space, and based a lot of his own fantasies on this shaky cardboard Creature. He was amazed when he viewed the film again in later years to see how totally tatty and unbelievable it was, and regarded his former enchantment with it as a triumph of the human imagination over very heavy odds. Plus the fact that he was nine when he saw it, and so had already experienced his life-transforming first visit to an art museum, when his mother drove him (nine hours each way on the road) to the nearest, in faraway St Louis, in the justified belief that now, aged eight, he was old enough to appreciate it.

It will be gathered that Parkes’s parents were not only impressed by his precocious talent, but also enthusiastically encouraged his interest in art. Whether they were all that keen on his becoming a fulltime, professional artist is another matter – but then, whose parents are? At least, they did not stand in his way, when he determined that the only way forward for him was to go to art school. And anyway, he did not elect to go to some airy-fairy art school, but to pursue a degree in a serious academic institution, where he could study Art History as well as the practice of Art itself. This meant that he would have the sort of qualification which allowed him to teach, a much more solid and reliable way of making a living than just painting.

And that, for some four years, he did: he took a good degree, and went straight on from graduation to become, first, an instructor in graphic techniques at Kent University, Ohio, then on to a better job at a university in Florida. Not only that, but he exhibited and had a fair measure of acceptance as a painter. And was he content with this degree of success in the eyes of the world? No, of course not. As a teenager he had become, as many did in the early 1960s, a searcher through the religions of the world, looking for the ultimate truth behind his dreams and visions. All that may have gone underground during his university years, but it had certainly not been eliminated altogether.

By 1970 he had reached a crisis point. This was, after all, the heyday of hippiedom, when everyone from the Beatles down seemed to be looking to India for enlightenment. Parkes had recently got married, to a young artist and musician called Maria Sedoff. Most people would see that as one of the traditional ways to persuade a restless young man – in 1970 Parkes was only 25 – to settle down, but instead he found in Maria a co-conspirator. Throwing up his teaching career, they set off with $800 in their collective pocket, for India (where else?) and hippie heaven. It may not have been quite heaven, but they lived there happily for three years, and it was only when they started a family that they felt that they would prefer their daughter to be brought up nearer to the amenities (especially medical) they had both been used to in their former life, and backtracked to Spain.

Curiously, teaching was not the only thing Parkes gave up when he left the States. He also ceased painting completely, feeling that it did not satisfy any of his deeper spiritual needs – or at least, not the way he was then doing it. In India, while they were studying Integral Yoga, the philosophy of Sri Aurobindo, and meditation, they had to make enough to live on somehow, and took up local kinds of handicraft, such as batik, jewellery and leatherwork. Designed to sell equally to tourists in India and back in Europe, they did very well – no doubt because their work stood out among the masses of hippie pseudo-crafts by virtue of Parkes’s superior imagination and sense of design.

So it might have continued when the Parkes family arrived in Spain. Except for one chance encounter. Parkes discovered that a friendly new neighbour was also an artist, and the first time he visited Manuel’s studio, a painting he saw there provided a Road-to-Damascus experience. Improbably, it was a picture of two horses in a stable, seen from behind, with the sunlight slanting down on them from a window. On one level it was a simple piece of rustic realism. But on another it seemed to carry an indefinable weight of symbolism: it had somehow passed through and beyond naturalism, to reach a different realm of strong but unfathomable emotion.